The Tunguska Explosion

Evidence of the mysterious blast 13 years after the cataclysmic explosion.

Had the following unexplained incident occurred today, even in the slightly relaxed atmosphere of the post-Cold War, it would have probably triggered World War Three. Fortunately, the greatest hammer blow from space to hit our Earth since prehistoric times happened when the 20th century was barely eight years old. Even today, scientists are still at loggerheads as regards to the nature of the extraterrestrial object which shook the world after exploding in the skies of pre-Revolutionary Russia.

The momentous event happened at 7.15 a.m. local time on the last day of June 1908. At that precise moment, an object brighter than the morning sun ripped through the atmosphere over Siberia. A trainload of passengers on the trans-Siberian railway stared in horror at the towering pillar of flame roared through the clear blue skies at a phenomenal velocity of around one mile per second. The sonic boom given off by the sky invader shook the railway track, convincing the engine driver that one of his coaches had been derailed. The driver jammed on the brakes and as the train screeched to a grating halt, the mysterious fiery object thundered north. The trembling train passengers listened in relief as the overhead danger became fainter, and many of them looked out the windows of the carriages and eyed the vapour trail with bafflement.

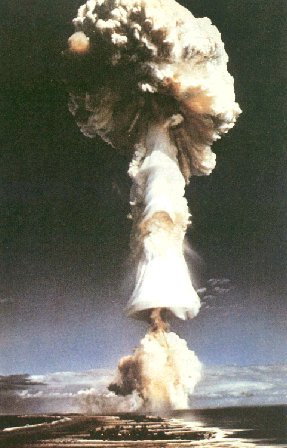

Almost 350 miles to the north of the train, the nomadic hunting tribes of the Evenki people felt the ground shake violently as they witnessed what seemed to be a second sun racing across the heavens. Only this sun seemed to be cyclindrical. By now, the immense apocalyptic object had been seen to change course as if it was being controlled or steered. After passing over the terrified travellers of the trans-Siberian train, the object made a forty-five degree right turn and travelled 150 miles before performing an identical manoeuvre in the other direction. The tubular shaped object then proceeded for another 150 miles before exploding over the Tunguska valley. The detonation occurred at a height of five miles, and the 12-megatonne explosion (it might have even been 30 megatonne) destroyed everything within a radius of 20 miles. Herds of reindeer were incinerated as they stampeded away from the explosion, and all wildlife in the area was ignited by the searing heat blast. Thirty-seven miles from the blast, the tents that the frightened Evenki people had taken refuge in were lifted high into the air by the resulting atmospheric shock wave, and the Evenki's horses galloped off in terror, dragging their ploughs with them. At the centre of the explosion a monstrous mushroom cloud rose steadily over Siberia. Such a strange and unsettling sight would not be witnessed for another thirty-seven years at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But this explosion was even fiercer than the A bombs which were dropped on the Japanese cities. The blast from the Tunguska explosion felled trees as if they were matchsticks for 20 miles around and set whole forests alight. The shockwave generated by the mysterious cataclysm travelled around the world twice and shook the recording pens of the microbargraphs at three meteorlogical stations in London, where they were interpreted as seismic jolts from some distant earthquake.

At a distance of 400 miles from the epicentre of the Tunguska blast, the relentless shockwave showed no signs of abating, and knocked fishermen from their boats on the River Kan. By the time the blast had deteriorated into a hurricane-like storm, a strange black rain started to fall over the Tunguska valley. Days later, strange scabs started to break out on animals that had been too far away to be directly burnt by the blast, and weeks later, curious investigators who ventured to the site of the explosion became sick and complained of strange burning sensations within their bodies. Were these signs of radiation sickness? But what meteoric object could be radioactive? Stranger still, why was there no crater at the site of the explosion? All meteorites leave a crater. And how would a meteorite travel horizontally for hundreds of miles and change course twice? Then there were other strange occurrences which seemed to suggest that the object which had exploded over Siberia was not a meteor at all, but perhaps some nuclear-powered spacecraft from another world which had had made an emergency crash-landing in a forbidding area of our world.

The first reports of a strange glow in the sky came from across Europe. Shortly after midnight on 1 July 1908, Londoners were intrigued to see a pink phosphorescent night sky over the capital. People who had retired awoke confused as the strange pink glow shone into their bedrooms. The same ruddy luminescence was reported over Belgium. The skies over Germany were curiously said to be bright green, while the heavens over Scotland were of an incredible intense whiteness which tricked the wildlife into believing it was dawn. Birdsong started and cocks crowed - at two o'clock in the morning. The skies over Moscow were so bright, photographs were taken of the streets without using a magnesium flash. A captain on a ship on the River Volga said he could see vessels on the river two miles away by the uncanny astral light. One golf game in England almost went on until four in the morning under the nocturnal glow, and in the following week The Times of London was inundated with letters from readers from all over the United Kingdom to report the curious 'false dawn'. A woman in Huntingdon wrote that she had been able to read a book in her bedroom solely by the peculiar rosy light. There were hundreds of letters from people reporting identical lighting conditions that went on for weeks after the Tunguska explosion. Scientists and meteorologists also wrote to the newspaper giving their opinions about the cause of the strange skyglare which ranged from the Northern Lights to dust in the upper atmosphere reflecting the rays of the sun below the horizon. No one connected the phenomenon with the strange object which had come down in Siberia to explode with the fury of a H-bomb. Even the national press in Russia gave no mention to the catastrophic even in the Tunguska Valley, because the country was then entering a major period of political upheaval. A serious investigation of the Tunguska incident did not take place for another thirteen years, when a Soviet mineralologist named Leonid Kulik led an expedition to the site of the explosion. But within those thirteen years, strange whispers and rumours spread across Siberia. There were tales of a strange being wandering the remote forests of Tunguska near the scenes of devastation. The nomadic reindeer herdsmen of Siberia sighted the gigantic grey humanoid figure some 50 miles north of the Chunya river. They saw the man, who seemed to be over 8 feet in height, picking berries and drinking water from a stream. The superstitious Mongol herdsmen regarded the freakish-looking stranger as one of the fabled chuchunaa - a race of hairy giants similar to the abominable snowman which were said to inhabit the region. The nomads crept through the forest to get a better look at the figure, and they saw that the grey colour of the man was not hair, but tattered overalls of some sort. The herdsmen sensed that there was something unearthly about the being, and they retreated back into the forest and moved away from the area. There were several more sightings of the grey goliath over the years, and each report indicated that the entity from the cold heart of Siberia was moving westwards. Alas, all of the accounts of the strange giant were interpreted as mere folklore tales of the Russian peasants.

In February 1927, Leonid Kulik went in search of the strange object that had impacted into Tunguska. He had read countless old newspaper clippings on the Siberian explosion and had conjectured that the object that had caused the widescale destruction had been a large meteorite made of stone and iron. Being a mineralologists, Kulik looked forward to obtaining samples of the meteorite for analysis. Kulik got off the Trans-Siberian railway at the Taishet station and on horse-drawn sledges they set off on an arduous three-day odyssey through 350 miles of ice and snow until he and his men reached the village of Kezhma, situated on the River Angara. At the village Kulik and his party of researchers replenished their supplies of food, then struggled on for a three-day journey across wild and unchartered areas of Siberia until they reached the log-cabin village of Vanavara on 25 March. Kulik then tried to make headway through the untamed Siberian forests, or taiga as the Russians call it, but was forced to turn back after heavy snowdrifts almost froze the horses to death. For three days Kulik was forced to remain in the snow-bound village of Vanavara, but during this period he interviewed many of the Evenki hunters who had witnessed the Siberian fireball's arrival on this planet. The tales of the sky being ripped open by a falling sun and of a great thunder shaking the ground made Kulik even more eager to penetrate the taiga to find his holy grail. When the weather gradually improved, Kulik set out for the Tunguska Valley. When he finally reached the site of the mysterious explosion, he was almost speechless. From a ridge overlooking the scene, Kulik took out his notebook and scribbled down his first impressions of the damage wreaked by the cosmic vandal. Kulik wrote:

From our observation point no sign of forest can be seen, for everything has been devastated and burned, and around the edge of the dead area, the young, twenty-year-old forest growth has moved forward furiously, seeking sunshine and life. One has an uncanny feeling when one sees twenty to thirty-inch giant trees snapped across like twigs, and their tops hurled many yards away.

Kulik then proceeded towards the felled forest, but two of the guides who had taken him and his assistants to the area refused to go any further. The guides told the bemused scientist that there was something or someone still lurking about in the area. Kulik thought the guides were superstitious fools, but they told him that strange things had been seen at twilight in the shadows of the dead taiga. The guides returned home and Kulik fortunately met a few bold members of the Evenki tribe, who took him and the researchers further into the taiga. By June, Kulik and his men had reached the middle of the explosion site, where uprooted trees were scattered from the centre of the blast like the tangled spokes of a wheel. There were no signs of a crater. Kulik realised that the explosion had occurred above ground. The Evenki tribesmen seemed to become very uneasy in the middle of the devastation zone, and started to talk about a supernatural presence in the area. But Kulik didn't have time to listen to such irrartional ramblings of the nomads; he had limited time to collect data for his friends back home at the Russian Academy of Sciences. There were three further expeditions to the site of the Tunguska explosion, all of them headed by Kulik. In 1941, Hitler attacked Russia. The 58-year-old Leonid Kulik volunteered to defend Moscow, but was wounded by the Nazis. He was captured by German troops and thrown in a prison camp where he died from his wounds.

The next three expeditions to the Tunguska Valley in 1958, 1961 and 1962 were led by the Soviet geochemist Kirill Florensky, who used a helicopter to survey and chart the blast area. Florensky's team sifted the soil in the area and discovered a narrow strip of dust which was of extraterrestrial origin. The dust consisted of magnetic iron oxide (magnetite) and minute glassy droplets of heat-fused rock. Florensky carefully checked the radiation levels at the site, but the only radioactivity present seemed to be from the fallout which had drifted into the area from distant Soviet H-bomb tests.

Scientists who examined the findings of Florensky and the data from further investigations of the Tunguska explosion site began to postulate that a fragment of Comet Encke had collided with our planet and smashed into Siberia in June 1908. Today, some scientists believe that the blast was caused by a wandering black hole or a chunk of anti-matter. However, there is one piece of curious evidence that seems to vindicate the spaceship theory. At the site of the Tunguska blast, there is a strange irregular shape at the centre of the circle of damaged terrain. Scientists and geologists who have analysed the shape say it looks as if it was caused by something exploding within a cylinder. Comets are not cylindrical, and they do not travel horizontally to the ground making forty-five degree turns.

And what of the fabled 'chuchunaa' creature? What became of him? The last known encounter of the grey giant took place in 1941 in Daghestan. A Colonel V. S. Karapetyan and his troops were called out to investigate sightings of an enormous 'beast-like' figure in the Buinaksk Mountains. The soldiers spotted what they regarded as a monstrosity and gave chase. They cornered the towering figure in a cave and opened fire on it with their rifles. The creature fell with a loud echoing thud, quite dead. Colonel Karapetyan later wrote an account of the confrontation with the unidentified human-like creature:

He stood before me like a giant, his mighty chest thrust forward. His eyes told me nothing. They were dull and empty - the eyes of an animal. And he seemed to me like an animal and nothing more...a wild man of some kind.

The corpse of the creature was left to to the scavengers, and the colonel and his men left the mountains and concerned themselves with the task of defending Russia from the Nazis. The humanoid they had killed may simply have been one of those mysterious 'men-beasts' such as the Yeti or Bigfoot, but according to some of the peasants of the Buinaksk Mountains, the oversized man wore ragged grey clothes. Is it therefore possible that the creature in the cave murdered by the military was the same being that had first been seen by the Evenki tribe near the scene of the Tunguska explosion? This leads us to a tantalising possibility; was the abnormally tall entity some marooned alien from another world who had managed to eject himself from a damaged spaceship after steering the craft away from the inhabited areas of Siberia? If this was the case, what a sad and barbaric end for a visitor who might have been able to teach us so much.