Tunguska: 91 years after the impact

By BBC News Online Science Editor Dr David Whitehouse

Scientists hope to solve the mystery of the greatest cosmic impact of the century by undertaking an expedition to a remote region of Russia.

The impact happened on 30 June, 1908, at Tunguska in central Siberia. With no warning, a small comet or meteor hurtling through space collided with the Earth and exploded in the sky.

The destruction photographed in 1938

The impact had a force of 20 million tonnes of TNT, equivalent to 1,000 Hiroshima bombs. It is estimated that 60 million trees were felled over an area of 2,200 square kilometres. If the explosion had occurred over London or Paris, hundreds of thousands of people would have been killed.

The first expedition to reach the site was led by Russian scientist L.A.Kullik in 1938. His team was amazed to find so much devastation but no obvious crater.

So began the mystery of Tunguska: What was the object that caused such destruction and why did it leave no crater?

Lake bottom

It may have been a small comet, made of rock and ice, that was fragile enough to be vaporised in the explosion before it struck the ground. Alternatively it may have been a low-density meteorite.

Even today some dead trees remain

To search for answers, the second University of Bologna expedition is about to travel to the isolated region taking with them a battery of high-tech equipment.

One of the team, Dr Luigi Foschini, told BBC News Online that one of their main aims will be the study of sediments at the bottom of Lake Ceko.

This lake is 8km (five miles) away from the centre of the 1908 explosion. The lake is about 500 metres wide and 47m deep.

Lake Ceko could hold clues

"We will be using a 'sub bottom penetration system,' to make a structural map of it to decide where to drill for samples from the lake bed," he said.

At the same time, a "side scan sonar" will take ultrasound photographs of the lake bottom. A remotely-controlled, underwater telecamera will also be used in the research.

Large fragments

Undisturbed samples will be collected by using a "box corer." Dr Foschini hopes to collect microparticles from the disintegration of the cosmic body to determine once and for all what it was.

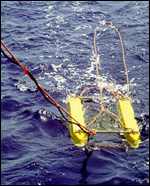

Testing the side-scan radar

They will also continue a search for microparticles preserved in tree resin. This was carried out on the earlier expedition in 1991. The researchers will also undertake an accurate aerial survey of the region and compare their data with that obtained in 1938 by Kullik.

The comparison between the 1938 pictures and the new survey should give further information on the direction of the trees felled by the explosion.

This microparticle was recovered in 1991

Some scientists believe that large fragments may have reached the ground before the main impact. If the cosmic body was a meteorite, then it may be possible to find these fragments.

A search will be made for them among the ground rocks of Tunguska using neodymium magnets together with a metal detector.